Daily Debrief 12 December 2024

In a nutshell

Today…

Tonga and Tuvalu emphatically reaffirmed the inalienable rights of their people to survival and self-determination, championing, in solidarity with Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), the continuity of statehood, the inviolability of territorial integrity, maritime baselines, and sovereignty as fundamental to self-determination. The Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA), AOSIS, Tonga, and Tuvalu highlighted the existential threats climate change poses to oceans and maritime zones, vital for Pacific livelihoods.

Timor-Leste, Thailand, Comoros, Tonga, and Viet Nam stressed the central role of equity in addressing climate change. Emphasising the link between colonialism, poverty, and inequality to the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibility and Respective Capabilities, they called for fair climate finance and technical assistance to redress historical and ongoing injustices. Thailand advocated for a just transition, ensuring no one is left behind when fulfilling State obligations.

Week 2, Question 2! Comoros, Viet Nam, Uruguay, and Tuvalu shared a focus on reparations and accountability, demanding financial and restorative measures for climate damage. Comoros, Viet Nam, Tuvalu, Uruguay, and Zambia emphasised the role of science in proving harm, establishing causation, and guiding reparations to hold polluters accountable.

Scroll down for all interventions!

Today’s reactions

“Tonga’s oral submission underscores the urgency of the climate crisis. It was great to see the government standing in solidarity with other small island nations, emphasising our disproportionate vulnerability despite minimal contributions to global emissions. Tonga’s call for clarification of States’ obligations under international law aligns perfectly with the call to action from civil society. We applaud the government’s emphasis on the principle of CBDR responsibilities and the duty to cooperate, which are crucial for achieving climate justice.”

- Siosiua Alo Veikune (25), Tonga, Campaigner, Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change.

“Comoro’s statement is a distress call in response to the suffering caused by climate hazards. Progress is not measured by words, but by actions and commitments to protect the most vulnerable, while ensuring true climate justice that does not overlook the lives of Small Island Developing States and does not compromise present and future generations. It is time for 'polluter pays' to cease being a climate utopia and to become a reality, for the voices of the most vulnerable to be heard, and for us to witness the establishment of genuine climate justice. Equity is not an option, but a fundamental right for all. Islander lives matter!”

- Lydia Halidi (32), Comoros, Biologist, environmentalist and climate activist.

Outside the Court

Photo credit: PISFCC

Today, three impactful actions organised by civil society actors highlighted the ongoing global call for climate justice:

The People’s Museum for Climate Justice, hosted by Greenpeace at the Zeeheldentheater in The Hague, is a collaborative space co-curated with communities disproportionately affected by the climate crisis. The exhibition, open until tomorrow, 13 December at 7 pm, features personal narratives, art, and interactive displays inspired by the ICJ advisory proceedings. Visitors can explore the resilience and struggles of those confronting climate change. A digital version of the museum is available here. Earlier this week, the exhibition also featured a private screening of Yumi – the Whole World, followed by a Q&A with film director Felix Golenko and Vishal Prasad, Director of Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change (PISFCC).

The People’s Booth organised by Interactive Media Foundation at the People’s Hub fostered critical reflections on the ICJ hearings’ aftermath. Through a collaborative bingo session, participants shared insights and outlined calls to action to maintain momentum.

Photo credits: CIEL

All the way over in Geneva, WYCJ, Earthjustice, CIEL, and partners hosted an event featuring UN human rights experts like Astrid Puentes and Elisa Morgera alongside activists Vishal Prasad and WYCJ’s Nicole Ann Ponce. The session unpacked key arguments from the ICJ hearings and explored lessons for advancing climate justice. The event showcased strong consensus among experts rejecting state attempts to sidestep legal obligations under the guise of a Paris Agreement "bubble" of unaccountability. Instead, the experts reaffirmed the centrality of legal principles, including the extraterritorial and intergenerational application of human rights.

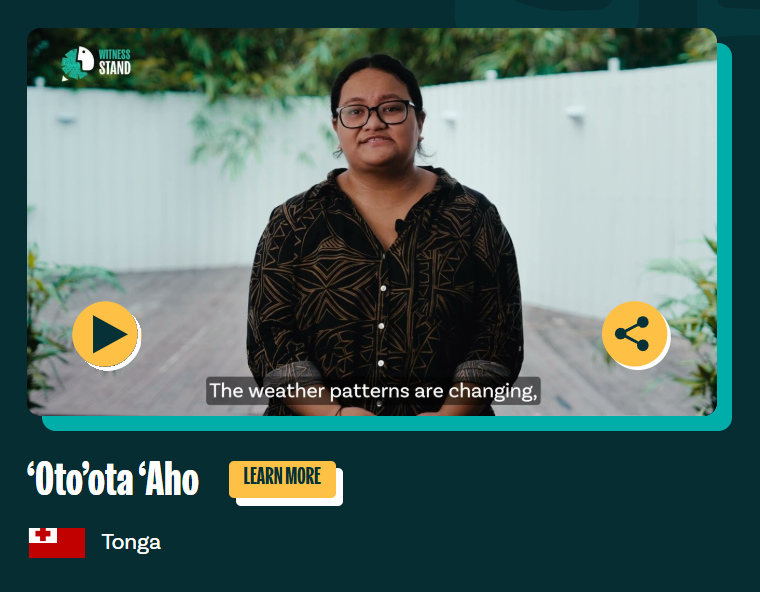

Witness stand

The Witness Stand was established to make sure that the on-going legal proceedings on climate change are more inclusive and representative of those most affected. The Witness Stand asks people from around the world what their message would be to the World’s Highest Court. Below watch and hear the stories of ‘Oto’ota ‘Aho, student, Tonga.

"We in the Pacific are living proof that the existing mechanisms, the UNFCCC, the endless conferences are simply not enough. We have seen countless promises, pledges, and funds, but they haven't been translated into real solutions on the ground. Every day, the news bombards us with the brutal reality of droughts, floods, heat waves, rising sea levels, and the devastating loss of life and biodiversity."

- ‘Oto’ota ‘Aho, student, Tonga

Report on Each Intervention

-

Thailand explained the impact that climate change is having on its territory and people and invited the Court to, when answering the questions before it, consider the voices of all States, clarify existing international law in a systemic and harmonious manner, and connect theory to practice. Thailand added that the climate treaties should be interpreted in light of pre-existing rules and treaties, including international human rights law, and that States have due diligence obligations to ensure the protection of the climate system through mitigation, adaptation, and cooperation, which are positive obligations of conduct. However, Thailand added that the level of due diligence regarding greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is stringent and objective, and should be informed by the best available science.

Thailand focussed on three aspects of the obligation of due diligence: equity in each State, equity across States, and equity across generations. On intra-State equity, Thailand urged the Court to consider the concept of ‘just transition’, which features in the preamble of the Paris Agreement and accordingly should be used in interpreting the obligations in that regime, including due diligence, with a goal to leave no citizen behind. On inter-State equity, Thailand submitted that the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC) means that all States should take measures, informed by the due diligence obligation, to address climate change — but to do so, developed States must cooperate with developing States, including through technical and financial assistance. Finally, on intergenerational equity, Thailand pointed out that the Paris Agreement instructs that climate action should take into consideration the interests of future generations, and stressed that this is also in line with the precautionary approach. However, it also submitted that the existence of “rights” of future generations is unclear, despite the rise in litigation asserting these rights, and thus invited the Court to clarify their status under international law.

Thailand’s mention of the precautionary approach was noteworthy, as few delegations have chosen to mention this important international environmental law principle. The focus on equity throughout the submission, and its connection with the obligations of due diligence in different realms, was too an interesting framing that could lead the Court to a progressive decision. Regrettably, Thailand did not venture into the question of legal consequences; however, it focused on the obligation of developed States to cooperate through financial and technical assistance, which could provide another basis for the much-needed tools for mitigation and adaptation in the Global South. Thailand’s position that the rights of future generations have yet to be clarified formally under international law (lex ferenda) was also too formalistic, especially in light of the wealth of existing studies and initiatives that already seek to clarify this right (notably, the Maastricht Principles on the Human Rights of Future Generations) — although Thailand’s request for the Court to address the status of these rights was a silver lining to this line of argumentation.

-

Timor-Leste highlighted its acute vulnerability to climate change as the 28th most climate-affected nation, suffering severe environmental, economic, and social impacts despite contributing only 0.003% of global GHG emissions. Timor-Leste detailed the challenges of its development, with over 48% of its population living in multidimensional poverty, and framed climate justice as inseparable from global poverty and inequality. It linked the climate crisis to historical injustices rooted in colonial exploitation and carbon-intensive practices by industrialised nations, arguing that these States bear overwhelming responsibility for the current crisis. Timor-Leste stressed the importance of the principle of CBDR-RC to ensure equitable climate action, arguing that Least Developed Countries (LDC) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) must retain access to the remaining carbon budget to support their sustainable development and right to self-determination.

On applicable law, Timor-Leste argued for harmonisation of obligations under climate treaties, customary international law, and other legal frameworks, declaring that climate treaties contain both substantive and procedural rules specifically tailored to address climate change and thus reflect the latest expression of State consent. It also asserted that prevention and other obligations of customary international law and human rights law, and under the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, complement the climate treaty regime but do not impose a more rigorous due diligence standard than that derived from the Paris Agreement. At the same time, it criticised the failures of industrialised countries to meet their climate finance obligations, noting the inadequacy of the $300 billion annual goal and the voluntary nature of the Loss and Damage Fund. Timor-Leste called for mandatory funding for Loss and Damage and debt forgiveness to enable vulnerable States to address climate change without undermining their poverty alleviation and development efforts. In relation to the prevention of transboundary harm, Timor-Leste argued that to prove a breach of this rule, States must show that there is a direct causal link between the conduct of a specific State and specific damage to another State.

Timor-Leste’s submission articulated a decolonial demand for climate justice but revealed several contradictions in its legal argumentation. While it emphasised harmonisation between legal regimes, its claim that due diligence obligations under the climate treaties are not strengthened by other applicable duties risks undermining stricter standards found in customary international law and human rights frameworks that may help hold polluters accountable. This approach would also provide States with wide discretion, and, for example, their GHG emissions would not be guided and limited by considerations of what constitutes the equitable use of the remaining carbon budget. Timor-Leste’s critique of voluntary loss and damage mechanisms highlighted the inequities in global climate finance but lacked concrete legal arguments to tie these failures to State responsibility under international law. By relying heavily on treaty obligations without sufficiently addressing broader legal principles, including the duty to provide reparations for harm, Timor-Leste risks contradicting its decolonial stance, which demands accountability from industrialised nations for historical and ongoing contributions to the climate crisis.

-

Tonga opened its submissions by framing the climate crisis as an existential threat to the natural environment, livelihoods, and culture of its people. Given the urgent need to take collective action to address the increasing risks and harms of the climate crisis, Tonga stressed that it is the ‘systemic integration’ of climate change treaties, human rights treaties, and all other relevant rules of international law that inform the legal obligations of States in respect of climate change. Throughout its submissions, Tonga highlighted the united front and leadership of the Pacific Islands in bringing forward the request for the Advisory Opinion, and on several matters of international law.

Tonga’s oral submissions focussed on three points. First, Tonga urged the Court to ensure that the principle of CBDR-RC informs the Court’s interpretation of State obligations in order to deliver outcomes that are consistent with the principle’s equitable nature. This includes taking due account of States’ capabilities and national circumstances. Second, and relatedly, Tonga argued that the Court must clarify the scope of the duty to cooperate, which relates to the provision of financial and technical assistance. In this regard, Tonga underscored that there is an explicit interdependency between the fulfillment by developed States of their obligations to provide financial and technical assistance and the ability of developing States to meet their obligations under the climate change treaties. Third, Tonga argued that the ICJ should affirm the presumption of the continuity of statehood and the preservation of State territorial boundaries instead and maritime zones in light of sea level rise. To that end, Tonga pointed out a strong consensus and well-established practice across multiple regions (opinio juris), including the Pacific Islands and Asia.

Tonga delivered arguments sensitive to the experience of SIDS. While Tonga did not directly address the second question on the legal consequences of breach, Tonga’s choice to emphasise the need to achieve equitable outcomes, particularly those in relation to climate finance and technical assistance, might be seen as a welcome addition to the arguments by Pacific Island States, which have thus far focused on the colonial histories, need for intergenerational equity, and nature of reparations in light of historic emissions. However, Tonga fell short by not urging the Court to clarify the critical human rights obligations and State responsibility in the context of harmful anthropogenic GHG emissions, a recurring theme emphasised by other climate-vulnerable States.

-

In its opening, Tuvalu highlighted this was its first appearance before the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The catastrophic effects of climate change on Tuvalu were powerfully underlined by their delegation, which noted how, despite producing less than 0.01% of GHG emissions on the current trajectory of emissions, Tuvalu is expected to be the first country to be completely lost to climate-related sea level rise. In moving video testimony, the direct personal experience of families losing homes and livelihoods demonstrated the existential stakes for Tuvaluans, illustrating the catastrophic harms that fundamentally interfere with their basic human rights. Tuvalu’s statement focused on two core legal issues: the right of self-determination and the implications of climate change for States’ rights of survival and territorial integrity.

Tuvalu focused on States’ individual and collective obligations to promote, respect, and protect peoples’ fundamental rights to self-determination from the existential threat posed by climate change. It argued that climate change threatens the Tuvaluan people’s way of life, cultural identity, and ancestral lands, expressing that “it cannot be that in the face of such unprecedented and irreversible harm, international law is silent.” Indeed, it is not; the right to self-determination is a cornerstone of international law, anchored in several treaties and customary international law. The ICJ itself has found that self-determination is a non-derogable, peremptory norm of international law with a broad scope of application extending beyond its historical origins in decolonization. Tuvalu was clear: its fundamental right to self-determination is being violated in the wake of devastating climate impacts. Tuvalu linked this violation to territorial integrity, noting that if Tuvalu cannot survive, its people’s free and genuine expression of their status and future becomes impossible. It also highlighted violations caused by the forced departure of peoples from their submerged lands and their dying oceans, urging the Court to address these issues for the sake of their survival. In a connected line of argument, Tuvalu’s counsel addressed the survival of States, linking the issue to the principles of State continuity, territorial integrity, and sovereignty over natural resources. Tuvalu called on the Court to require States to: first, act to stop transboundary harm before it is too late for Tuvalu and its people; second, increase financial contributions to least-developed and climate-vulnerable States; and third, preserve statehood by ruling that maritime baselines must remain fixed, despite physical changes to coastlines due to sea-level rise.

Tuvalu’s oral intervention was a sobering one that threw into stark relief the absolute urgency, scale, and devastating impacts of the climate crisis. Tuvaluans are doing everything they can to preserve their nation from extinction through land reclamation activities. They are even exploring a “digital Nation initiative” to “recreate” Tuvalu’s land, culture, and government in digital form. Meanwhile, throughout the hearings, major polluters have engaged in playing the legal system to prioritize narrow self-interest, doing their utmost to evade and dilute their legal duties — whilst other States face the threat of disappearing altogether. It is time to break this cycle of harm and impunity. The Court has a solemn responsibility to hear Tuvalu’s call to keep the right to survival and the right to self-determination at the very center of its critical advisory opinion. The delegation quoted a Tuvaluan climate activist who powerfully said: “Tuvalu will not go quietly into the rising sea.”

-

The Union of the Comoros opened its submissions by highlighting that it is one of the island States most vulnerable to climate change despite its negligible GHG emissions, highlighting the efforts that have been taken to combat sea level rise and salinisation. Its counsel emphasised the interconnectedness of law applicable to climate change by urging the Court to take a systemic interpretation of the entire corpus of international law to find that State obligations in respect of climate change are complementary and not conflicting. They further argued that the Paris Agreement and the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) establish collective obligations for mitigation, adaptation, and cooperation, with a clear emphasis on differentiated responsibilities — with a particular emphasis on financial and technical assistance to achieve equity and intergenerational justice.

Comoros highlighted that customary international law, including the no-harm rule and the duty of due diligence, requires States to prevent transboundary environmental harm by implementing measures proportionate to their resources, capabilities, and scientific knowledge. It argued that the due diligence obligation has evolved to demand robust and context-specific actions, as evidenced by the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea’s (ITLOS) interpretation of the duty in its recent climate advisory opinion. Comoros also argued that human rights law imposes positive obligations on States to adopt measures addressing climate change due to its adverse effects on human rights, including the right to self-determination. Comoros contended that States are responsible for preventing transboundary harm affecting individuals outside their territory if there is a causal link between their activities and the harm, and if they exercise effective control over those activities. Comoros underscored that climate change threatens the territorial integrity and survival of SIDS, arguing that these threats constitute a breach of States’ unalienable right to survival.

Regarding State responsibility and reparations, Comoros argued that the failure to adopt necessary measures to prevent harm from GHG emissions constitutes an internationally wrongful act, one that breaches obligations owed to the international community as a whole (erga omnes). It stressed that reparations must follow such breaches, including cessation of wrongful acts, compensation for loss and damage, financial support, capacity building, and adaptation assistance. Importantly, Comoros refuted excluding responsibility for pre-UNFCCC emissions by asserting that such emissions represent continuing and composite acts under customary international law, which encompasses obligations predating the UNFCCC framework. Moreover, on causality and the plurality of acts, it underscored that anthropogenic GHG emissions were caused by the cumulative actions of multiple industrialised States. In this sense, Comoros argued that customary international law provides a framework for addressing collective and individual State responsibility. Comoros urged the Court to apply the polluter pays principle, noting that the share of responsibility for harm should be determined based on each State’s individual contribution to global emissions. It also urged the Court to confirm that breaches of climate obligations, especially involving multiple injured and responsible States, need both accountability and loss and damage mechanisms.

The Union of the Comoros, despite not submitting a written statement, delivered a powerful plea for climate justice by rejecting arguments from industrialised States and major polluters while advocating for the interconnectedness of climate law, the law of the sea, and general international law. Comoros rightly called for robust accountability mechanisms to address the cumulative harm caused by GHG emissions. Aligning with the Commission on Small Island States for International Law on Climate Change (COSIS), Comoros underscored the existential threats of climate change that breach unalienable rights to survival, territorial integrity, and self-determination. It urged the Court to clarify State responsibility, including in relation to reparations, compensation for loss and damage, and equitable accountability for collective harm. Comoros stood resolute in calling on the Court to deliver an Advisory Opinion that upholds the rights of the most vulnerable and ensures justice for those disproportionately affected by the climate crisis.

-

Uruguay’s oral statement underscored the scientific consensus confirming that anthropogenic GHG emissions are the dominant cause of climate change; this is no longer a mere future threat, but the reality we face today. The submission highlighted two main arguments: (1) the applicability of the duty of prevention and the duty to cooperate in light of the principle of CBDR-RC, and (2) the existence of clear legal consequences for States that breach these obligations.

Uruguay submitted that States had an indisputable duty to use all means at their disposal to prevent serious or irreversible damage caused by GHG emissions from sources within their jurisdiction or control to the environment of another States. Given the conclusive scientific evidence of the causes of climate change and the harm inflicted on the environment, it argued that the long-standing duty to prevent transboundary harm to the environment clearly extends to harm caused by GHG emissions. Uruguay observed that in light of the precautionary principle, this duty also exists in the absence of full scientific certainty with respect to the potential damage to be prevented. The duty of prevention is not superseded by the climate treaties, it argued, but rather applies jointly with, and illustrates, States’ specific obligations under such treaties.

On legal consequences, Uruguay asserted that where significant harm has been caused to the climate system and other parts of the environment, States can be held accountable for their breach of an obligation under the general rules of State responsibility, as already supported by the ICJ’s case law. Such obligations involve cessation and reparation duties. It emphasised that this customary obligation applies jointly with specific financial obligations under the UNFCCC, and that meeting the obligation under the law of State responsibility does not absolve States from having to continue meeting their obligations under the climate treaties. While recognising the challenges in establishing a causal link between specific acts and omissions and harm, Uruguay argued that such complexity does not absolve States of their duties to provide reparations when they fail to uphold their obligations. It further stressed that not all State obligations require material harm or damage in order for that obligation to be considered breached.

Uruguay presented well-reasoned legal arguments in support of climate justice and countered many points raised by a minority of States, particularly in relation to the applicability of the longstanding duty to prevent GHG emissions and the legal consequences that arise when obligations are breached. For instance, in direct contradiction to an argument made earlier by Timor-Leste, Uruguay highlighted an often overlooked reality that there is no general requirement of material harm or damage as a requisite for determining State responsibility for breaching their obligations. Similarly, Uruguay underscored the undeniable scientific evidence regarding the causes and consequences of GHG emissions, countering arguments that allege that climate change is too complex to establish State responsibility for harm to the climate system.

-

In its opening, Viet Nam emphasised that it is a low-lying developing State highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Its people face an increasing number of climate change impacts, including deadly tropical cyclones. This includes the devastation wreaked in 2024 by the most powerful and destructive supertyphoon to hit Viet Nam in 70 years, which killed more than 300 people, injured nearly 2,000 others, and resulted in an estimated 3.3 billion US dollars of damage to the country’s economy.

In answering the first question before the Court, Viet Nam firmly rejected the argument that the climate treaties were lex specialis, urging the Court to follow the principle of systemic integration and harmonisation to find that State obligations in respect of climate change are found across the entire corpus of international law. This includes the principle of CBDR-RC. Viet Nam also made specific arguments as to the standard of conduct under the duties to prevent significant harm and to cooperate. On the standard of conduct, Viet Nam stressed that the due diligence obligations must be based on the available scientific and technological information, the urgency of the risk at hand, and the severity of the damage suffered — all of which ‘science is clear on’. On this point, Viet Nam also welcomed the initiative of the Court to meet with scientists before the commencement of the oral hearings. On the duty to cooperate, Viet Nam argued that the climate treaties are not exhaustive of State obligations to cooperate, as the duty is also found in customary international law. The relevance of the CBDR-RC principle to the climate context also means that factors such as the transfer of relevant technologies, conservation of carbon sinks, and adaptation needs must be taken into consideration when determining whether that duty has been fulfilled.

In answering the second question before the Court, Viet Nam reiterated that instruments of international law beyond climate treaties, such as the International Law Commission’s (ILC) Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, are relevant to determining the legal consequences for breaching state obligations in respect of climate change. Importantly, Viet Nam rejected the view that historic emissions were excluded from any liability regime, as the principle to prevent transboundary harm was established before much of the significant emissions in modern history.

Viet Nam affirmed the role of science in establishing a causal link between GHG emissions and the harms suffered to the climate system. Furthermore, it elaborated that while States may be collectively responsible for the ultimate damage, they may still be held individually liable under the doctrine of the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts. States would then be obligated to cease such intentionally wrongful acts and make reparations for the damage caused. Viet Nam further maintained that the principle of CBDR-RC was relevant when ordering cessation or reparations in terms of guiding the extent and nature of the award. The extent of the award must be informed by the historical emissions and financial and technical means of the State. The nature of the award would depend on the respective capabilities of the State and the nature of the loss suffered. Viet Nam clarified that reparations are not limited to monetary compensation and should also involve restorative measures for the national environment, support for mitigation and adaptation efforts, measures to prevent the recurrence of the harm, and other forms of assistance to build climate resilience.

Viet Nam was especially sensitive to the role of science before the Court, particularly the ways in which loss and damage varies across the natural environments of States. This understanding of available scientific information should inform the Court’s assessment of the causal links between State actions and environmental harms, and the type of remedy awarded. Viet Nam’s arguments on the role of CBDR-RC were also comprehensive, providing many examples of the ways in which States differed in their financial, infrastructural, and scientific capacities. However, while the principle is doubtlessly relevant for interpreting obligations in respect of climate change, caution should be heeded for its application to the legal consequences of breach. CBDR-RC cannot be a scapegoat for developing or less-able countries to escape responsibility for environmental damage. Unfortunately, breaches of human rights and harms caused to future generations were not raised in Viet Nam’s oral submission. -

Zambia emphasised a shared legal and moral duty to preserve a sustainable planet for future generations, focusing on the effects of the climate crisis on its economy. Allocating over 30% of its national budget to debt repayment has severely hampered Zambia’s ability to invest in climate adaptation, mitigation, and loss and damage measures — from building resilient infrastructure to developing green energy solutions. Climate-induced droughts and declining river levels have strained critical sectors, including agriculture, tourism, and energy, forcing increased reliance on coal as hydropower diminishes. Zambia’s submission made three key arguments. First, it stressed that climate obligations extend beyond the Paris Agreement and the UNFCCC. Second, it underscored developed States’ duties to equitably reduce GHG emissions and provide support to developing States for adaptation and mitigation. Finally, Zambia called on the Court to apply its jurisprudence and the ILC’s standards on State responsibility to climate change, urging clarity on legal consequences, including reparations.

Zambia asserted that obligations to reduce GHG emissions arise not only from the Paris Agreement but also from customary international law, with the principle of prevention constituting a due diligence obligation recognised under the Paris Agreement. The principle of CBDR-RC must guide the equitable allocation of emissions reductions, which Zambia asked the Court to clarify. Zambia further argued that developed States have a positive obligation to support developing States’ mitigation and adaptation under CBDR-RC. Current practices, such as repurposed humanitarian aid or concessional loans, fall short of States’ positive obligations to provide support. As part of reparations, Zambia proposed alternative finance mechanisms, including debt relief, grants, and debt-climate swaps, which it argued are more appropriate than loans. Zambia also argued that State responsibility offers a flexible framework for addressing the complexity of climate change, recognising wrongful acts in aggregate, holding multiple States accountable regardless of shared responsibility, and emphasising that liability does not depend on causation or damage. States must cease wrongful conduct, provide reparations, and fulfill their obligations. Zambia underscored that causation is not a bar to responsibility.

Zambia addressed the Court with a clear claim: climate justice necessitates a comprehensive interpretation of State obligations, extending beyond the Paris Agreement and the UNFCCC. Drawing on customary international law and the ILC’s Draft Articles on State responsibility, Zambia highlighted that developed States’ obligations include equitable GHG reductions and increased support for adaptation and mitigation in developing countries, as guided by the principle of CBDR-RC. Furthermore, Zambia underscored the applicability of the regime of State responsibility to climate change, citing Article 47 of the ILC’s Draft Articles and the Court’s jurisprudence on reparations. Zambia urged the Court to clarify legal consequences, including debt relief, as essential to overcoming barriers to achieving climate resilience. Zambia’s plea reflects its belief that when Africa loses, the world loses, but when Africa thrives, the world thrives with it.

-

The Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) explained that climate change is heating the oceans, causing deoxygenation and acidification, with adverse effects on coral reefs, shellfish, and fish populations. Large-scale bleaching events caused by marine heat waves and acidification are harming coral reefs and associated fisheries. The most important Pacific fishery from an economic perspective is that of tuna, which has been sustainably managed in this region, unlike in other parts of the world. Yet climate change is causing tuna populations to shift eastward out of the exclusive economic zones of Pacific Island States and into the high seas, putting the sustainable management and economic benefits of tuna for these States at grave risk.

The FFA explained that with almost half (47%) of Pacific Island households dependent on fisheries for some or all of their income, the climate crisis threatens the livelihoods, food security, and economies of Pacific SIDS. Other adverse impacts include loss of culture, erosion of Indigenous and local knowledge, and negative impacts on traditional diets, food security, and health. Some coastal communities have already been forced to relocate. Unless there are rapid and major declines in GHG emissions, climate impacts on fisheries will continue to worsen in the coming decades. There will also be severe declines in biodiversity, which may further undermine food security, livelihoods, and cultures.

The FFA emphasized the profound economic, social, and cultural dependence of SIDS on healthy oceans. The climate crisis is already having extensive negative impacts on oceans, harming fisheries, livelihoods, food security, health, culture, biodiversity, and national economies. In closing, the FFA called on the international community to take urgent action to reduce GHG emissions to counter the profound economic, social, and cultural threats of ocean pollution.

-

The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) comprises 39 small island and low-lying coastal States that are acutely vulnerable to the damaging impacts of the climate crisis on people, communities, cultures, ecosystems, safe water supplies, food security, and livelihoods. The impacts already occurring include rising sea levels, coastal erosion, salinization, and ocean heating. AOSIS noted that adaptation measures, such as desalination facilities, are expensive. It emphasized four points in its submissions: the need to take into account the disproportionate impacts of the climate crisis on SIDS; the duty of cooperation, including financial and technological assistance, as a general principle of international environmental law; the duty of States to recognize the stability of maritime zones; and the principle of continuity of statehood and sovereignty. AOSIS urged the Court to evolve the interpretation and application of international law to confront new realities.

AOSIS made extensive submissions regarding the stability of maritime zones, calling on the Court to confirm the conclusions of several recent international declarations that the rights and entitlements flowing from maritime zones shall continue to apply without reduction, notwithstanding any physical changes caused by climate change-related sea level rise. It also urged the Court to affirm that statehood, once established, endures despite physical changes or even complete inundation of a State’s terrestrial area due to climate change-related sea level rise. AOSIS concluded that it would be the pinnacle of inequity and contrary to the principles of justice underpinning all of international law if SIDS were to lose their statehood, sovereignty, and memberships in international organizations because of the acts of other States.

The compelling submissions of AOSIS explained why the profound existential threat posed by the climate crisis to nations’ territories, peoples, and cultures should not pose an existential threat to their statehood. Because rising sea levels may cause the partial or complete inundation of some SIDS, particularly low-lying atoll nations, AOSIS made forceful arguments about preserving existing maritime boundaries and maintaining statehood and sovereignty. These submissions, driven by concerns about the very survival of some States, reflect the high stakes and extraordinary significance of the Court’s Advisory Opinion on legal obligations and consequences in the context of the climate crisis.

Tomorrow

Tomorrow, Friday, 13 December, we will report back on the oral submissions delivered by: Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law, Pacific Community, Pacific Islands Forum, Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States, World Health Organization, European Union, International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Important Notice: These Daily Briefings are aimed at highlighting an early summary of States’ oral submissions to the International Court of Justice. It provides critical elements for context to understand the significance of key arguments made to the judges. These briefings are not meant to be legal advise and do not give a comprehensive summary of the arguments made by each State or Intergovernmental Organisation appearing before the Court. Please refer to the video recordings and the transcripts for a full rendition of each oral submission. The Earth Negotiations Bulletin also offers daily reports from these oral hearings which can be accessed here.

This Daily Briefing is provided by World’s Youth for Climate Justice, the Center for International Environmental Law, and the AO Alliance, supported by a group of volunteers.

The lead editors of today’s Daily Briefing are Aditi Shetye, José Daniel Rodríguez Orúe, Nikki Reisch, Sébastien Duyck, and Theresa Amor-Jürgenssen.

The contributors for today’s Daily Briefing are Danilo Garrido, David Boyd, Erika Lennon, Joie Chowdhury, Justin Lim, Mariana Campos Vega, Noemi Zenk-Agyei, Prajwol Bickram Rana, Quint van Velthoven, Richard Harvey, Rossella Recupero, Upasana Khatri, and Yasmin Bijvank.

Our deepest gratitude to all those who helped with taking notes during the hearings: Ambre Zwetyenga, Dulki Seethawaka, Jeli Santos, Juliette Dessagne, Katie Davis, Noemi Zenk-Agyei, and Zainab Khan Roza.